لا عنوان

Le correspondant ne répond plus à cette adresse

Souad Abdelrasoul, Viyé Diba, Abdoulaye Konaté, Ghassan Salhab, Ousmane Sow

13 SEPTEMBRE - 08 NOVEMBRE 2025

OH GALLERY, DAKAR

Pour inaugurer sa saison 2025-2026, OH Gallery réunit Souad Abdelrasoul (Egypte), Viyé Diba (Sénégal), Abdoulaye Konaté (Mali), Ghassan Salhab (Liban) et Ousmane Sow (Sénégal) dans l’exposition لا عنوان, le correspond ne répond plus à cette adresse.

À travers des œuvres plastiques, filmiques et installatives, les artistes interrogent l’expérience du déplacement dans toute sa violence structurelle. Dans un contexte global marqué par l’intensification des mobilités humaines, choisies ou contraintes, les artistes explorent les dynamiques complexes envisagées ici comme expérience du corps et de l’identité, mais aussi comme vecteur de transformation, de mémoire et de résistance.

En croisant des trajectoires géographiques, l’exposition met en lumière l’impact des contextes sociaux et politiques d’origine dans les processus de migration, les tensions entre territoire et appartenance, entre frontières imposées et espaces vécus tout en interrogeant les héritages postcoloniaux et les systèmes de domination qui organisent la circulation des corps et continuent de façonner les imaginaires autour de l’exil, du retour, ou de l’impossible départ.

AVANT PROPOS

PRÉSENTATION

The Vacation Program: gesture & address par Moad Musbahi (merath)

Version originale en anglais

The Arabic "لا عنوان" can be translated as referring to something that has no title, literally as untitled, or it can be a clause that refers to a thing that has no address, no known location of referral. To address [someone / something], as an active verbal condition, is perform a gesture that aims to mark out a name, a title or some identifier that expects acknowledgement or a refrain.

The art works on display at OH gallery aim to work through the placelessness of being somewhere to the fleeting gestures that suture and define belonging. They collectively question, the ‘not having’ of; an address, a name, a body, a cartography; or the deferral of these attributes from which to question what is the site of performance and return to the ‘having of an address’.

To think the address as a gesture as I will aim to in this piece, is the desire to destabilize the overstudied and exhausted subject of migration on the African continent and Western Asia. The topic has ceaseless impetus, as the forms of border policing, state violence and ethnic cleansing develop ever more violent technologies to displace, as they aim to tirelessly expand the category of the ‘displaced’. Just the desire to be on the move, or to be perceived as having such a desire, has been foreclosed as a criminal intent [1]. In this piece, I take this opportunity to think with the artists, to trouble what it means to avoid addressing someone as ‘the migrant’, and consider the case of migration more laterally. Put simply, I aim to read this exhibition with the motivation to shift an understanding of migration from a fact (of illegal movement) to a case (of mobility).[2] This opening up, the literal and metaphorical crossings of perception and expectation, about how people travel, and move is multi-temporal and non-linear, geological and generational time never follows the fictively steady meter of the clock. It builds on my experience as I first came to Senegal, visiting the cities of Dakar and Touba in 2021, on an art residency to engage with how different communities in Senegal learn how to move and what are the many forms of teaching that incorporate travelling as necessary part of their pedagogy. Key to this experience, and as I continue working as an artist, and writing on art works, is to see the value of thinking with others, and to do that thinking on the move. [3]

The fact / case distinction I evoke is my reading of Fred Moten’s reading of Fanon. The fact for Fanon is the imposition of violence, of being named, fixed, externalized under a gaze that precedes you. But the case, for Moten, becomes something else entirely, a site of resistance, of unfolding, of black study. The case holds within it not only the evidence but also the capacity to refuse its own terms. I am using this essay to consider if migration as verb that produces the subjectivity of ‘migrant’, can be unpacked along similar lines, if it too holds this tension, between the fact of migration, which is used to delimit, surveil, and reduce, and the case of migration, which is its own mode of study, movement, and disruption. The fact is what gets counted at borders, archived in applications, and flagged by software. The case is the route that detours, the breath held in a customs line, the lineage carried not in documents but in stories, names, omissions. If blackness, in Moten’s sense, is a kind of lawless law — something fugitive yet binding — then can migration, too, be not just movement across borders, but an ongoing theory of motion, one with history, futurity and a political aesthetic to reclaim, an endless gesture that exceeds the limitation of the reductive term ‘migrant’. A simple evocation of this line of thinking is by how names are given not just to places or people, but to routes. I spent time in Touba learning about the different journeys of Sheikh Amadou Bamba, and how each route in his exile was a named story that founded a community, these stories became an itinerant resource about itinerancy.

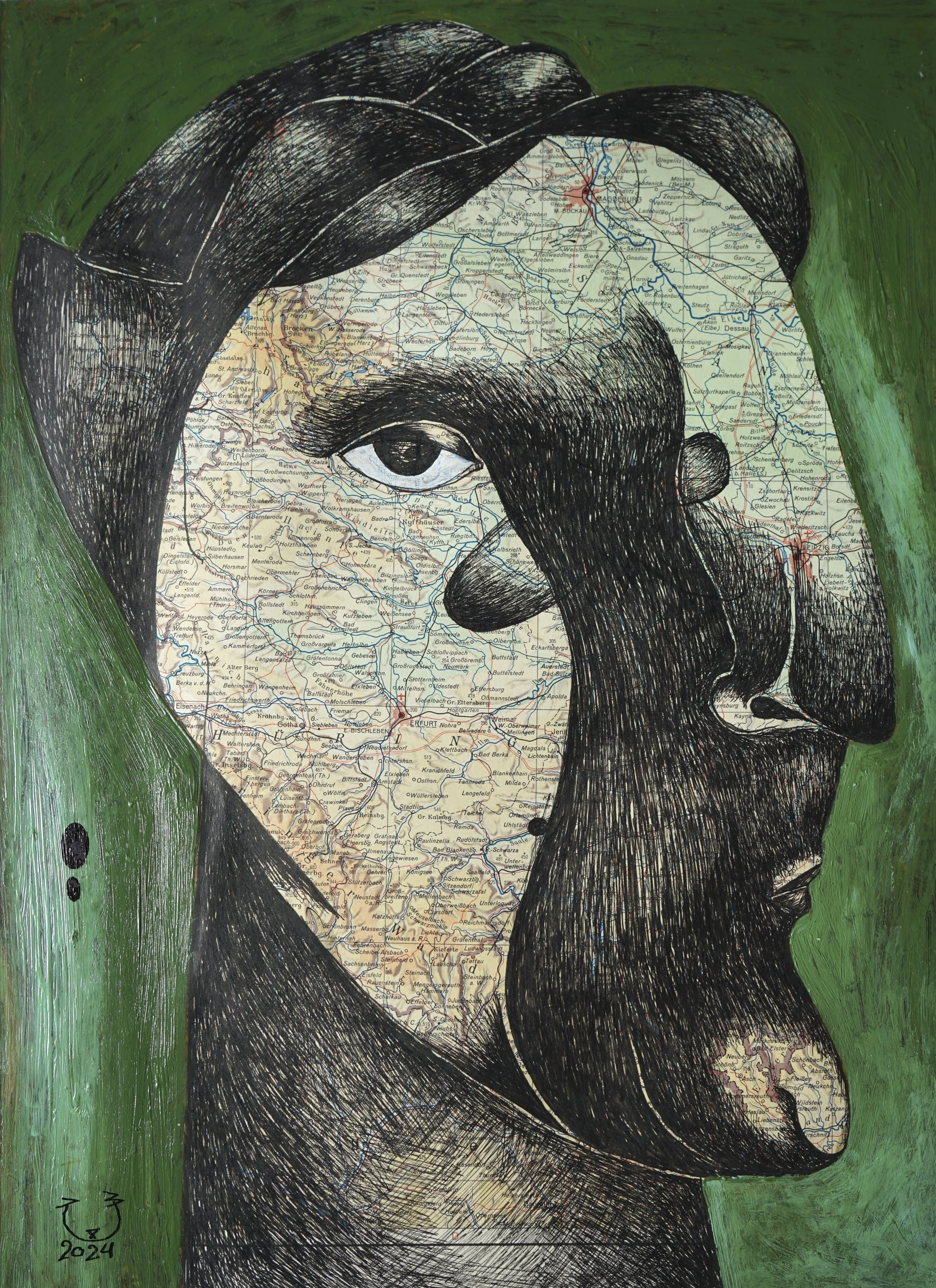

In Senegal, contemporary journeys to study continue and are frequent, to Morocco, to Egypt where religious followers go. Such journeys have a long precedence in the Sahara and are given names. This practice of naming routes inverts the sensibility of a place as a set of fixed relations but encompasses a thinking about the places one carries with them. This practice is a result of how the ground is marked and given a quality by those who have passed through it. This is powerfully evoked in the drawings of Souad Abdelrasoul. The series of works blur cartography with physiognomic identities that at first sight, you see a face as an address, a map as a person, of a place you cannot discern but that contains geographies of a multitude. Adelrasoul extends this from a collage of characteristic features of a map and parts of a face into play on the instability of recognition, a move where the eye sees double. By testing the threshold of what you see with the aesthetic representation of elevation (her medium is topography, a palette of raised features), turning these characteristics of raised relief into a caustic work that refuses to stay put, unfixing the address at the level of their beholder, swapping between the mood, expression and emotion of the land, and the geography, structure and points of the face. Through this process Abdelrasoul, for me, asks, what makes a mountain and what makes an eye, and in the same move, questions, she goes on to more deeply probe, what makes a person, what makes a place?

I AM OUT OFFICE

As an artist working from commission to commission, moving from residency to residency, there have only been a few times I’ve had to set up an ‘out of office’, and they have all been during moments when I not been moving, when I haven’t worked as an artist. There is a kind of certainty of return when one sets up their own ‘out of office’ email, something fixed, the ‘office’ that allows one to be ‘out of’ it. It is a certain privilege of locate-ability, of having an ‘office’ and the somewhat oppressive demand to acknowledge the addresser in the act of being addressed (in an email).

The typical out of office aims to give a date from when you’d return to create a future expectation of reply and return or an alternative email to address your timely inquiry. This deferral in time and deviation of direction is bound up in the surety of the subject, I exist and I will return. Put differently, you found my address (the electronic mailing address, email, the location from where I can be reached at any time), and yet I am not here, at this time now, and I expect to not be here soon enough for you to not feel my absence (or I want to declare that I am not here, even if I really am here), but with the firm conviction that, yes, you have sent me a message, that I will be back, I will respond and that I will then be reachable once again, I will be at my address as usual.[4] Receiving the automated reply, it immediately evokes an image of all the other emails that are floating unopened in the inbox, awaiting to be answered, and that person far from their desk, oblivious to your addressed concern, ignorant of the demands you are piling.

The function is relatively straightforward, building on the social decorum that it is not good ethics to leave an email unanswered for too long, that the addressee will be offended left unaddressed, in short if they called on you and you left them hanging. Unlike the telephone, a knock on my front door or the exclamation of being called by my name on the street, the letter and its more contemporary electronic variant demand a different response when the addressee does not acknowledge the address. How many times does it happen that when someone calls, and I realise they got a wrong number, where then I simply state that fact and hang up the telephone. Just before the confession, I am not who you say I am, who you thought I was going to be, I have no further time to give you, there is a moment of being called by a name that is not my own that troubles my sense of self, the hesitant pause, the momentary silence of the addresser knowing something about the addressee, about me, that the addressee does not know about themselves, something I did not realise about who I am. In Dakar I would commonly hear my name, Moad, pounced as Maad, an honorific title in Wolof, but quickly realise I am ‘hearing things’. It can be quite a geographic concern, that the addressee thinks I am this other person, because they found me here, in this place and actually, I am not where I am meant to be.

In an email, the need to keep the message moving propels me to forward it along, I tell them they need to reach out to someone else, someone with a different address. Not that they made a mistake with my location (the address that they emailed would have ‘failed to deliver’ otherwise), but they mistook who I am, what I could do for them.

When this function was first invented in 1983 by Eric Allman it was called the ‘Vacation program’. Such a naming suggests the perception of its American user who is sending and receiving emails, is an office worker whose fixity to their desk was only interrupted by a moment of leisure time, while on holiday.

What I am trying to think with here, is how something like the ‘out of office’, or vacation program, as it was first invented crystallised and imported these conceptions of having an address, of being addressed, and yet creates a tenuous culturally specific state that fixes the two, an address and addressing, in the case of the out of office email. I think through this flurry of correspondence as it is evoked by the work by Viyé Diba, sheets of pen on paper, hung across the gallery, contained in plastic sleeves. Letters, typewritten documents and drawings litter the space, as the work, Dossiers de Candidature à l'Immigration, makes you navigate the scene in haphazard directions, glaring light into the crinkled plastic, questioning, where was the artists attempting to go, what were the notes taken in a waiting room awaiting one’s turn with a consular interview, or the marks that turn the application’s paperwork into something more meaningful than the banality of state bureaucracy. The plastic sleeve guarding against the degradation of time, as one awaits a response, some sent with marks of the postal service fading seal and others clearly carried in the pocket for some time, the folds worn enough to tear the sheet in pieces.

ADDRESSING TO REMOVE AN ADDRESS

In the original documents descripting how to use the Vacation program, the authors suggested an alternative use case, “The vacation program is also useful as a graceful way to retire users while keeping their account open for a while.”[5] Picture the situation, someone gets fired but the company keeps their account and puts in a pre-made response announcing their removal to anyone who aims to correspond with them. The use of the term graceful is sinister, replacing what I imagine was the melodrama of a physical departure from an office, boxes and all, by the automated function of a cold calculating robot. The slow criminality of co-opting the address is present if I return to thinking of Moten’s Fact/Case dialectic that he develops from Fanon, specifically, drawing from a now well-read passage from Fanon, that begins with the moment a child identifies him with the remark, “Look!” and proceeds to deny his subjecthood with the racial violence of the address, giving him a name, title, defined only by the colour of his skin. I don’t need to repeat the terms here from Fanon, or this passage that has been much studied, but the role of interpellation, a capacious term that contains the consequences of the ‘to address’ action I am circling, is necessary to unpack, and one that features often in the momentary voice overs in the moving-image work of Ghassan Salhab.

Driving around the south of Lebanon in the aftermath of the destruction of the Israeli bombing, Salhab takes you on a journey through a road that was cleared - were they the roads or simply a space where the community pushed the debris away? There is little to no voice over, fragmentary correspondence breaks up the drone sound of the car and the solemnly quiet activity of gathering belongings from between the rubble, as the misshaped concrete silently speaks volumes and amplitude. The destruction wrought here is only a fraction of the scale of the decimation that Gaza has faced. It is day 705 of the genocide in Gaza and no matter of words, art or theoretical framing can ever be worthy to address the death and disaster that is wrought by the Israeli state. This is not an attempt to think of the dead that have yet to be mourned, and I do not place it in the passage of an essay about an exhibition to draw on any of its concrete reality that far exceeds words, but in the spirit of Palestinian scholar Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian [6], there is a demand to take on the tools available to us as thinkers and artists to better know how this destruction is wrought, to declare and excavate and materially address, what is even happening that exists at many layers of psychological and existential power, intentionally hidden from view. The violence is so pervasively expansive that it is important to name it, and name all of the different wounds it is inflicting.

As the artist Salhab documents this aftermath in Lebanon, I am drawn to the small moment he asks for directions, places to go that are perhaps unknown to him from before, but certainly beyond recognition as the rubble and a reminder of a place that once stood tall. The people seem familiar with him and do not question his presence but simply give him some of the updated ways of getting there. This is in stark and jarring contrast to the Israeli policy of ‘direction giving’, an ironic and disturbing policy of dropping leaflets above the inhabitants of Gaza and Lebanon, telling them, addressing them, to leave their homes.

The leaflets are dropped to people located at a zone, with full awareness that the address will be obliterated.[7] It is further, the need to refuse the possibility of ‘having an address’ where denying the locatability of the Palestinian or native citizen, is one that falls within the ethnic cleansing project. The leaflet works by informing them of the imminent destruction of their address, and to move to another one, for now. If I take us back from Fanon to here, let me dig further into what is the double role of being addressed, as interpellation is doing. Interpellation is the moment one becomes a subject by being hailed — called into being by a force that precedes them. Fanon’s experience of being named Black under the white gaze is a classic example: not a recognition, but a designation, an external definition that insists on being internalized, the moment you are called not to be known, but to be managed. The leaflet falls within the case of interpellation as it is given, through the airdrop, as an address. To refuse the leaflet drop, to refuse being addressed by the Israeli state in this mechanism, is to be caught in the accusation by the Israeli army that you are a guilty figure. The fact that if one did not heed this leaflet that was addressed to them in this location, that one had to move to another location, but rather one remained in their place, is determinate of their supposed complicity with the ‘enemies of the Israeli state’. That the only conclusion of refusing the address from the perspective of this aggressor disguised as an addresser is noncompliance and thus total forfeiture, in all its interpretations.

Moten complicates this supposed reality of interpellation, of being addressed by refusing the totality of that naming, suggesting that even as one is hailed, one can echo, blur, or mishear the call. The subject is formed in that moment of address — “Hey, you there!” — but there’s a slippage, a noise in the call. The leaflet is a case of interpellation stripped bare: there is no illusion of equality or dialogue. It is pure command, addressed to those who were never meant to answer, only to obey. The violence is not just in the threat, but in the grammar — in the way the state assumes it has the authority to name, to direct, to address and thus make a people without an address.

This example of the leaflet airdrop over Gaza and Lebanon is a monologue disguised as communication, a gesture that treats the recipient not as a subject who can respond, but as a problem to be moved, a presence to be erased. In this sense, the address is not about reaching the other — it is beyond even claiming the space in which the other exists, it is about effacing the capacity to address the other. It is an address that simultaneously names, displaces to then destroy, that says you are here, but only so it can say you must go, and in turn to then erase the you from the potential of ever being addressed again. There is an ongoing madness in this deployment that is beyond any scope of an essay to account for. What I am attempting to do, and in reading the work of Salhab driving through the destruction in Lebanon, is to think across the ways these technologies of address and interpellation are developed through prior colonial formations and in many places. Technologies of address that are also as seemingly neutral as the protocols of an email, that in reality construct and determine our contemporary understandings of place and placelessness, person and personhood. Technologies that have a situated history and are in fact never neutral.

An example of this performative violence emerges in the moment a person is named a migrant, a name used by parties of the border police as well as the humanitarian organization, parties supposedly on opposites sides of the moral spectrum. Unpacking this calling on the ‘migrant’ further is beyond the scope of this experiment, of thinking on the move, but I write this passage while I am in Janzour, Libya, and recoil at every instance of referral to someone as ‘the migrant’, the person with a story and specificity, reduced to a violently reductive label, a label that processes and categorizes them as it names them. The name, migrant, is given by a xenophobic impulse defined more by how it effaces of a figure’s personhood by addressing a disparate group equally, even in the face of different legal statuses, ethnic and linguistic belonging, and many many other distinguishing realities and divergent desires. Moten reminds us that there’s something before and beyond the call — a prior disorder, an ongoing noise — that resists full capture. Who is the migrant, but a term that gives a privilege to the perspective of the state’s object of policing, where even in ‘helping the migrant’ one keeps them in this bind? What is the cohesion that draws a people on the move together, that allows them to be in correspondence and in dialogue and not be made into a group to be managed by a set of borders? What are the names we can give people or communities on the move, that takes seriously migration as a case and not as a fact? Names are powerful objects and addressing someone with their name needs to be more carefully considered, as a consideration for a person’s history, their future, their desires for return, that addresses their own unique case of migration or calls upon a theory of motion that is more capacious than what the bureaucracy of a border can possibly contain.

CODA ON CORRESPONDENCE

In this piece, and with these artists, I am not trying to collapse the realities of disaster, I do not speak of migration as if being on vacation or seeking refuge are comparable conditions, but I seek to more critically understand the capacity of being on the move as an agency afforded for people to shape, an auto-biographical propensity. The act of address and this theory of motion I am invoking cannot be singular or fixed; the body finds itself called into being by many voices, inhabiting multiple addresses at once, and yet I cannot give privilege to the term migrant when it keeps the voice of state and its border apparatus as a persistent echo. The address is always cacophonous and Interpellation fractures identity, scattering it across different places, languages, and expectations. This is vividly reflected in and inspired by the work of Ousman Sow and Aboudlaye Kanté, whose practices explore the instability of belonging and the multiple layers of identity that resist easy categorization.

Sow’s installation traces the movement of bodies through shifting terrains, capturing the way presence is dispersed across time and space. Similarly, Kanté’s work grapples with the tension between visibility and invisibility, calling attention to how bodies are addressed and misaddressed by histories, borders, and social narratives. Together, their work reveals how the body is not tethered to a single address but exists in a dynamic correspondence, responding, resisting, and reshaping the calls it receives. In this multiplicity, the artists open a conversation on the possibility for new forms of belonging and connection that are not confined by conventional borders or categories. This ongoing negotiation resonates deeply with the lived demand and practice of a ‘right to return’[8]—as a fixed destination and as a continual reimagining of belonging, a refusal to be confined by displacement or erasure, and a persistent assertion of presence beyond imposed boundaries. Through their art, Sow and Kanté remind us that the body’s address is always provisional, always in flux, and always capable of rewriting itself. For them, the body is malleable, and it is made in part by how it is named, which importantly involves also how one addresses themselves.

A case of migration would need to hold on to the desire of where wants to be and who wants to be. Even if one is not at home, or in many homes, it is important in this discussion to remain thinking, and to remain on the move. It is to say, I can determine where I will have an address, of where and how I want to be called upon.

notes

[1] https://theconversation.com/travelling-across-the-sahara-has-become-a-crime-98324

[2] The critique that takes place from a fact of something to the case of something is utilized by the African American scholar Fred Moten in his discussions of Franz Fanon work, particularly the essay Moten, Fred. “The Case of Blackness.” Criticism, vol. 50, no. 2, 2008, pp. 177-218

[3] Undertaken with RAW Material Company with the Harun Farocki Institut.

[4] Consider the parallel of this technology with the invention of ‘hold music’ during the development of the telephone.

[5] Costales, Bryan, and Eric Allman. Sendmail, 3rd Edition: Theory and Practice. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Addison-Wesley, 2007. Chapter 5, "Vacation Program."

[6] Shalhoub-Kevorkian, Nadera. “Ashlaa’ and the Genocide in Gaza: Livability against Fragmented Flesh.” Hot Spots: Anthropology in a Time of Genocide: On Nakba and Return. Society for Cultural Anthropology, October 31, 2024.

[7] Forensic Architecture. Inhumane Zones: An Assessment of Israel’s Actions with Respect to the Provision of Aid, Shelter, Safe Passage, and Assistance to Evacuees in Gaza; Response to Questions Raised in the ICJ on 17 May 2024. London: Forensic Architecture, 19 May 2024.

[8] Andaleeb Adwan (2024). Changing Concepts of Return: Palestinians Between the First and the Present Nakba. Society for Cultural Anthropology.

AUTOUR DE L’EXPOSITION

O H L I B R A R Y

- L A B I B L I O T H È Q U E N O M A D -

Rencontre avec La Bibliothèque Nomad

Samedi 11 octobre 2025 de 15h à 18h

P R O J E C T I O N S

- C E N T R E Y E N N E N G A -

Jeudi 25 septembre à 19h

Jeudi 16 octobre à 19h

Jeudi 06 novembre à 19h

Œuvres

À PROPOS

-

Souad Abdelrasoul

-

Viyé Diba

-

Abdoulaye Konaté

-

Ghassane Salhab

-

Ousmane Sow

© Quentin Dauvergne

À PROPOS DE MOAD MUSBAHI

Moad Musbahi est un artiste qui travaille à travers l’installation sonore, le film et la sculpture. Il est membre de merath, un collectif curatorial basé entre la Libye et l’Algérie. Il co-dirige Taught to Travel, un projet artistique pluriannuel en collaboration avec RAW Material Company et le Harun Farocki Institut.

Son travail a récemment été présenté à Hayy Jameel, Djeddah (2024) ; à la 2e Biennale de Diriyah (2024) ; à La Casa Encendida, Madrid (2024) ; au Kunstverein, Hambourg (2023) ; ainsi qu’à la 14e Biennale de Venise (2023), entre autres.

Moad est membre associé du Centre de Recherche en Économie Appliquée pour le Développement (CREAD) de l’Université d’Alger. Il prépare actuellement un doctorat conjoint en anthropologie et en humanités interdisciplinaires à l’Université de Princeton, et enseigne les arts visuels, les études sonores et l’anthropologie.